[Missed Chapter 3? Read it.]

When I got rid of everything I owned and left America, hopping on a plane and flying to Berlin, my passport had only ever been stamped by visits to two other countries: Canada and Belize.

I’ve always read broadly and cared about the rest of the world and dreamt of visiting far-flung places and cultivated international friendships, but I am less worldly than I may seem when measured from the vantage point of basic nation-state geography.

Touching down in Berlin and seeing myself represented as a pulsing red dot on the screen on my phone, 6,000 miles away from where I was used to seeing myself, with a huge ocean in between, drove home the point that I had travelled very far. Zooming out and looking around the map showed me how much more I had to explore.

I’d better get going. I had a job to find.

A job search with a tough deadline

A month before I left San Francisco, I began carpet bombing Berlin-based companies with my CV, across a wide spectrum of industries and organisations. I made it as clear as possible in all of my correspondence that I would be in Berlin for three months so it would be no problem at all (you just say the word!) for me to stop by their office or grab a coffee with them at a nearby cafe.

That effort paid off. I was rewarded with a steady stream of video chats and a few actual in-person interviews during my first month in Berlin: a classical music app, an e-commerce platform, an early-stage startup with vague ideas and a whole lot of funding, a European fashion brand, a book-oriented subscription service, too many agencies to name.

I was seeking work as a copywriter, although not necessarily at an agency, which had never appealed to me. But I also knew that I might have to pursue a freelance visa if I wanted to stay in Germany, so agency work wasn’t out of the question. Pursuing a freelance visa (Freiberufler) would have been both more costly and less lucrative than getting hired with a company-sponsored work visa, but more importantly, it doesn’t guarantee long-term residency in Germany.

You can’t just pick up and move to any country you want, and Germany has a world-famous bureaucracy. You either have to get pulled in by an employer or find a way to push yourself through the channels that exist. Pushing through is a harder road, but not impossible. I spoke to anyone who would give me their ear and their time.

Living where East met West

When I arrived, I initially stayed at my friend John’s apartment in Prenzlauer-Berg, which has two balconies and a sweet vinyl record collection. John is a painter, which is not an easy thing to be in today’s world, which seems to only want to embrace more of the digital and the ephemeral (aka the scrollable). He and I used to work together at a restaurant back in my university days in Athens, and I volunteered to watch their cats while he and his wife Petra were on vacation, before moving into my tiny sublet apartment.

My tiny sublet was also in Prenzlauer-Berg, which might be the coolest neighbourhood in Berlin. It juts up against other centers of youthful coolness, Friedrichshain, Kreuzberg, and Mitte. On Sundays, nearby Mauerpark is the place to be, with its popular flea market. Before the Berlin Wall came down, this place was a “death strip” on the East German side of the wall with floodlights, dogs, and trip-wire machine guns ready to shoot anyone who tried to escape. Where once there was certain death, now there is a carnival atmosphere, with hordes of expats, hipsters, and local weirdos sitting on trampled grass and drinking out of enormous bottles of beer, which they open with their teeth. A piece of the wall still sits here. It’s used for graffiti practice.

I think the East Berlin vibe is what makes Prenzlauer-Berg so special, although it has also been significantly polished by gentrification. It’s got loads of adorable shops and cafes. Being able to traverse the city on my bike again and again helped me see the economic dividing line the Berlin Wall used to impose, and perhaps still does in some ways. Some of the brutalist Soviet architecture in the former East Berlin, in particular the gigantic and impressive socialist blocks of worker apartments on Karl-Marx-Allee in Neukölln, is in surprisingly good shape.

Cycling the city and beyond

After my bike arrived from San Francisco in its cardboard box, I spent hours every day cycling around the city, which is massive. It was still bitterly cold at the beginning of March, so I bundled up in as many layers as I could without wearing a bulky coat. I added two pairs of gloves, a scarf, and a cycling helmet, which was actually my cousin Amy’s hand-me-down ski helmet. She gave it to me the year before when I visited her in Idaho on my six-week camping sabbatical around the Pacific Northwest. It had already served me well on my chilly winter rides in San Francisco, and its built-in ear coverings allowed me to stay out for many hours, until my feet froze.

If you ever need a cycling helmet for winter, buy a lightweight ski helmet. They are much higher quality than typical cycling helmets, and much more comfortable. Women’s helmets are usually less bulky and often more comfortable still. They usually have well-designed ventilation holes so a ski helmet can be used until it gets hot in late spring.

Some of the roughly cobblestoned and pock-marked streets of Berlin are painfully tough on a bike with skinny tires, but in general it’s a good place to cycle. Over the last decade, they’ve been adding more and more cycling lanes, although not nearly enough protected bike lanes. Still, there are lots of places where bicycles and pedestrians intermingle but cars don’t, like Tempelhofer Feld, the former airport landing strip turned public park.

A third of this city is green space, and the parks are legendary, but unfortunately cars still reign supreme in Berlin and the rest of the country. The Germans really love their autos. I really don’t. I definitely felt like I should be wearing a helmet while cycling on the streets of Berlin, although I don’t enjoy wearing helmets and would prefer not to.

Although a lot of public art and sculpture was destroyed during WWII, you can still find buildings and outdoor spaces that are practically medieval. There’s art around every corner in Berlin, or at least graffiti - more graffiti than you ever thought possible. Even trees sometimes get tagged. While much of it is amateurish and sophomoric, there’s no denying that it helps define the city. The combined effect of graffiti covering practically every visible surface, on the side of trains and all along the track corridors they travel, splashed onto every exposed industrial girding or pipe, gives Berlin its rough and tough – possibly dangerous – character.

My aim wasn’t just to see graffiti and public art. I also cycled far out into the countryside and to nearby cities, stopping at manors and castles that are sometimes interconnected by rustic forest trails. I tried to cover as much ground as I could when I wasn’t applying for jobs, studying German, and keeping up with a few freelance writing commitments to keep my funds from draining too fast. I kept extra busy by squeezing in trips to nearby cities.

Traveller of strange paths, if not worldly ones

To think that I had, at this late age, finally gone trans-continental gave me a feeling of satisfaction and even a fair bit of wonder.

I wasn’t a world traveller because I grew up in the deep South, where I was surrounded by communities of people who were suspicious of both outsiders and change. I don’t think anyone I knew in Georgia even had a passport, although I had met a few people who vacationed in Hawaii. The idea of my family being able to afford a flight to another country was far outside the realm of possibility. Besides, why bother when you can just drive down to the Redneck Riviera in Florida?

And drive we did. As a child, nearly every Friday evening my family and an amateur crew of drunken good old boys would hitch a trailer holding a stock car to the back of our van, pile in, and drive overnight across multiple states, listening to country music on the AM radio, all so my stepfather could drive his race car around in a circle for two days. On Sunday nights, we’d drive back home through the night, returning a few hours before school began.

You see, I grew up in “the pits”, the greasy donut holes of dirt racetracks. When I wasn’t exploring rusty, industrial, highly flammable environments with feral packs of newly-met redneck kids, Lord-of-the-Flies style, I was reading books and magazines. All of that time spent on these road trips led me, an only child, to cultivate an avid and precocious reading habit, along with a powerful love of old-time, twangy country music.

I think losing myself in books and a tendency to daydream came partly out of that childhood experience of continuous travel. Reading all those books ultimately led me to the idea of attending university, which is something no one in the history of my extended family had ever done before. I also think that my itinerant youth – my family had a habit of moving every few years – instilled in me an enjoyment of exploring new landscapes. Although, when seen from a negative perspective, this probably translates into mercurial flightiness and a fear of long-term commitment. This is why I may never own my own home. If life punches me down for a year or two, I want the freedom to cut my ship loose and set sail for new adventure.

Since my childhood, I’ve visited 30 of the 50 US states and crossed the width of North America more than once in a car without air conditioning, but that boast feels sadly provincial when compared to the historic footprints you can follow in Europe and the multitude of cultures you’ll cross when trying. I thought I had seen a thing or two out there on the highways and by-ways of America, but exploring Europe looked like an entirely different challenge for a basic and important reason: Strangers almost always spoke English in my past travels.

Wo ist das WC?

Not everyone in Germany speaks English, of course. When you’re a stranger in a strangely vocalised land, it’s easy to feel dumb and hopeless when you’re trying to communicate something more advanced than, “Where is the toilet?” If you’re going to live in a different country, you need to get comfortable with daily mustering up the courage to approach a local with only a handful of poorly memorised phrases and a belief that you can make the conversation go where you want it to go. This is an important feeling of helplessness that I think most Americans don’t experience, but one they probably should.

I don't believe there is anything in the whole earth that you can't learn in Berlin except the German language. – Mark Twain, “The Awful German Language”

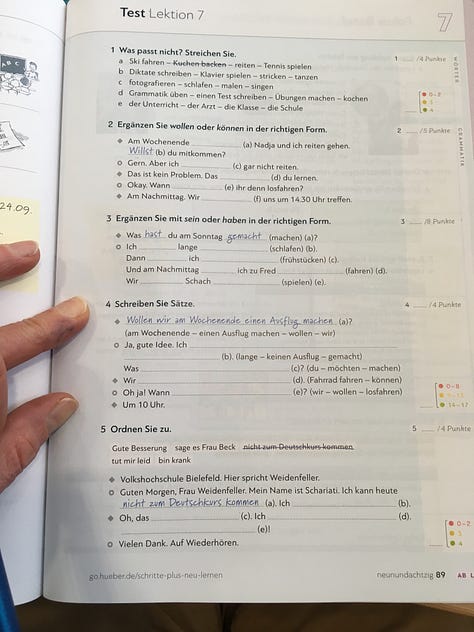

Since I wanted to lose the feeling of being a foreigner as quickly as possible, I committed to a six-week intensive German class in Mitte. The problem was, I’ve never been very good at learning other languages. I’m a natural at English. I studied literature and creative writing at university, and publishing words has essentially been my life’s work ever since, but I don’t enjoy diagramming sentences because I don’t have an analytical mind. Being good with words in English comes to me intuitively, but that doesn’t work when you need to learn a new language. You’re forced to dig into the tediousness of grammar. And no peoples of the Earth enforce picky grammar rules like the Germans.

Easter in Hamburg

For Easter weekend, I took my bike on the train to Hamburg to visit my old friends Sven and Heike, who live in Rahlstedt, an almost off-the-grid area east of the city.

Years earlier in San Francisco, my son Henry and I shared a house with Sven (Austrian) and Heike (German) and their two toddlers on super-steep Bernal Hill. Our back deck had a spectacular view of downtown San Francisco. One of the real joys of later parenthood is reconnecting with the teenage or adult versions of little kids that you used to know. Their youngest, who was actually born in the house we shared (that’s very German), could barely speak when I last saw her. Now, both children were practically teenagers, perfectly fluent in English, and just as wholesome, honest, and outgoing as their parents.

On Saturday night, we all rode our bikes to a special event, an Osterfeuer. Germans have been holding Easter bonfires for centuries, and it’s especially popular in northern Germany. Some of these bonfires start with massive piles of wood assembled into place using forklifts, so they can reach epic heights, while others are less dramatic neighbourhood get-togethers. When the flames rose high and somebody pulled out a guitar and started a sing-a-long in German, it started to feel like a pagan celebration out in the countryside, with adults drinking beer and kids wrapping strips of raw dough around sticks and roast their own “stockbrot”. It’s not as tasty as marshmallows, but it is thoroughly German.

A different kind of portfolio

As always, my cover letters helped me get noticed, but I also sent prospective employers a unique style of portfolio. I created a three-page document, written as a casual but business-focused narrative with photos and charts and graphs. It read like a breezy blog post (much as I’m communicating with you right now), and it explained my history of work, my challenges, my successes, and exactly what I was seeking right now as a travelling copywriter looking for a place to thrive in Europe. Throughout the piece, I peppered links to archived pages of some of my best work, links that I had been diligently archiving over the years, whenever I published something I was especially proud of.

Whoever said anything you put on the Internet stays on the Internet forever has never tried to submit a creative portfolio of their published online work. Almost everything with my byline in the last 20 years, from newspapers to magazines to blogs to forums, has long been erased from the collective hard drive. The companies either go out of business, get acquired, or stop paying their hosting bills.

In my little story about me, I included Google Analytics that showed the growth of blogs I had created and grown. One of them, a blog for a drawing app, I grew to 1.4 million pageviews per month within two years. In even less time, I grew an Instagram following for a photo app to 250K people, without paying for bots, thank you very much. Would you want me to do something like that for your business?

As you’ve no doubt surmised, I’m a bit of a boaster, but only because I’m proud of the work that I do. I’m just as quick to point out my flaws and imperfections, whether you want to hear them or not – always in the name of balance. I know that my arrogance and straightforwardness turns some people off, but I feel like life is too short for you to hold back your true thoughts and feelings. I want to find a real connection between me and the person who will be my boss. When you’re looking for a job, I think radical honesty is the best way. It can prevent you from becoming stuck in a situation that you don’t want later on.

That said, radical honesty doesn’t always work. When a recruiter ends your interview with the phrase, “Let me give you a piece of advice…” you know you definitely didn’t get the job.

I didn’t send this document to all prospective employers, just the ones who looked like they valued creativity and hard work, which isn’t everyone. Despite what they might claim in job advertisements, most companies are not actually looking for innovators and disruptors. They’re looking to fill a role that requires a specific set of skills, and they don’t always want people who will push boundaries or upset the status quo. If they didn’t like my style, I trusted they would close the window and move on to the next applicant. But quite a few took the bait.

A quick jaunt to Amsterdam?

Three months seems like a long time for a vacation, but if you’re looking for a job, it’s only 12 short weeks. I knew that hiring an expat always takes months and months of paperwork, but I kept moving forward anyway, even as I heard the clock on the proverbial wall ticking more loudly each day.

I fired off more CVs to cities across Germany and to other locations around Europe. In my research, Amsterdam kept coming up, perhaps because the city was benefitting from Brexit’s looming deadline. Brexit was the biggest political self-own in modern history, and it was encouraging many influential London-based businesses to uproot their HQs and reestablish them in more tax-friendly – and immigrant-friendly – European cities. “Is Amsterdam the new London?” read the headlines.

I had never been to Amsterdam, but the city wasn’t hard to get to. I had already sent my little work-story CV to a few Dutch companies, and it had even resulted in two phone interviews. I didn’t know that much about Amsterdam beyond the typical stories of weed and prostitution, one of which interested me and one of which didn’t, but I knew the Netherlands was one of the most bike-friendly places on the planet.

That was really all I needed to know. I wanted to see this cycling paradise for myself. I found a cheap flight and booked a last minute hotel room in the nearby city of Haarlem, which was cheaper than Amsterdam. It also provided me with an excuse to ride 20 km to the city and back on a rented bike.

How could I have known how important that decision would be?