Het inburgeringsexamen: the Dutch citizenship tests

I passed all of my Dutch citizenship exams. Now what?

Ik ben geslaagd!

I received a letter in the post recently letting me know that “I passed” all five of the citizenship tests – het inburgeringsexamen– which are essential to becoming a citizen of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Hoera!

My delightful neighbour Vera, who is Dutch, wished me “gefeliciteerd” with a bottle of champagne one Friday night. We celebrated by listening to Dutch songs and chatting the night away in tipsy English and Dutch and singing to her cat Momo, who stays with me when Vera goes on vacation every summer to Turkiyë. I help her with her cat. She helps me with my Dutch.

Although I’ve been studying Dutch for what seems like forever, I still feel like I have a long way to go before I can have authentic, lengthy conversations with real Nederlanders. At my rate of study, it could be another year, or even two, before I’m fully fluent.

Getting schooled in Dutch

The intensive Dutch classes I’ve been taking for a few years now crush me with their difficulty. I’m slow and old, a daydreamer with a foggy memory.

Every class is five weeks of brain-melting struggle, but also fun weekend field trips in different neighbourhoods, along with a few borrels (drinks and snacks) at cafes around De Costabuurt, where the school, Koentact, is located. Some nights we have lengthy classes, and the rest of the nights I spend scribbling out huiswerk by hand that will probably never even be graded, but that I know is good for me.

I meet fascinating young people from all over the world in these classes. Most of the time, I’m the only American in the room, as well as the oldest person in the room, including the teacher. They must think I’m a curious person, which I am. I don’t hesitate to be direct and ask them all kinds of probing questions like, “What did you want to be when you were a child, and what do you do now?” Only in Dutch, of course. You can ask young people questions like that as you get older. They feel obligated to answer you.

At some point, we all have to get up in front of the class and tell stories in Dutch about our own life and journey to this country. That’s my favourite part of the classes, except when it’s my turn. I started wearing glasses last year, which make me look smarter in Dutch than I actually am. They give me a tiny boost of confidence against the overwhelming glare of attention in these situations. I hate being the visible center of attention. I only want to be admired or examined from afar.

Last week, I went to Mezrab, a cool storytelling club on the Veemkade that has both Dutch and English speaking nights. I regularly ride by the entrance to the building on the Veemkade many times per week because it’s on my regular cycling route, but I had never been inside. Francisca was there to tell a story about her love of Africa, and I stopped by while on a ride to support her. It was the first time she had ever spoken in front of 150 or so people. She performed it in English, which isn’t even her first language. She’s braver than me. When I get up in front of class, I sound like a precocious five year old in my half-learned second language.

I’m completely drained by the end of each course. Sometimes I have to stop and take a break (een pauze) from Dutch, which I’m doing right now. By doing it this way, learning bit-by-bit instead of running one long marathon, I probably just extend my goal of fluency further out into the future, but it’s nice to drop back in after skipping a round. I’m almost always reunited with old classmates and teachers. (“Wat leuk, het is mijn favoriete docent Bart/Esther/Iris/Lucy/Ot/Marie-Pierre/Tim!”) I’m always running into former teachers around the school building, and it’s a real boost of confidence when I chat with them and show them how far I’ve progressed, from speaking Dutch like a toddler to conversing as well as a seven-year-old.

Ik heb een pauze nodig

In December, I took a break from classes because I felt like I was finally ready to tackle the integration exams. I signed up for a different test every week. They are entirely in Dutch.

There are five tests: listening, speaking, reading, writing, and Knowledge of Dutch Society. The best way to study for each test is to grind through all of the practice exams the government provides, which are just older versions of the tests.

A typical test question, which focus heavily on Dutch values and norms: You watch a video of Minke listening to her boss giving her a series of instructions on how to open the store by herself in the morning, and then you answer a series of questions about whether or not Minke understood what her boss told her to do, and in what order. I’ve heard some expats complain that the tests contain racist or otherwise objectionable portrayals of immigrants, but it may simply be that these low-budget morality plays are crudely constructed, preaching with good intention but little tact. I can relate. That’s how people at work probably see me.

The answers are mostly common sense, but you can make a lot of mistakes by not understanding what they’re asking, not having a strong enough vocabulary, or by using shitty grammar. To prepare, I made lists of typical sentences I would need to use in my answers based on the practice test scenarios: making an appointment to get your bike repaired at the fietsenmaker, looking for a job and going on an interview, being honest when someone asks you a question, calling out people in public who make fun of homosexuals (goed zo!), and the most important lesson of them all: making certain that you are never, ever, ever late for an appointment.

I waited many, many weeks for the last two test results: speaking and writing. Both of these tests must be graded by real people, not computers. I was worried I might fail because I’m extremely bad at following directions and can’t keep things simple. I overcomplicate my answers to questions, which is not a very Dutch trait. Giving more information than is necessary in your answer only increases the number and severity of the mistakes you make.

For example, there’s no need to sound smart or clever when answering the question, “Why was Minke late for the appointment?” The answer is simply: “Minke was late to the appointment because she had to wait for a drawbridge.” And yet, I can’t help myself. I want to be able to explain Minke’s plight with context, subtlety, and verve.

Was the sun out? Did she take a moment out of her day to enjoy this unexpected pause, parking her bike and walking over to the canal and leaning against the bricks, dreamily watching the shipping boats glide by, like I sometimes do? Was there a flower stall by the drawbridge (there always is) where she might have bought a small bouquet of tulips and hung it on her bike basket just before the bridge lowered back down?

The strictly timed tests also award efficiency, which is a very Dutch trait. Unfortunately, I excel at dilly-dallying.

Failing wouldn’t have been a catastrophe. You just have to spend another 50 euros to retake each test. I passed them all and am waiting for my official diploma, which I expect will arrive by mail in another month or two.

It’s been a long road to obtaining Dutch citizenship, but it’s not over yet, for two reasons. First, I can only apply for naturalisation after I’ve been in the country for five years, which for me will be on 16 September. Yes, I know the exact date without having to look it up. Second, I suppose I could change my mind at the last minute. I’m almost certain I won’t. I’ve thought about these issues deeply and have a long list of reasons why I want to leave America forever.

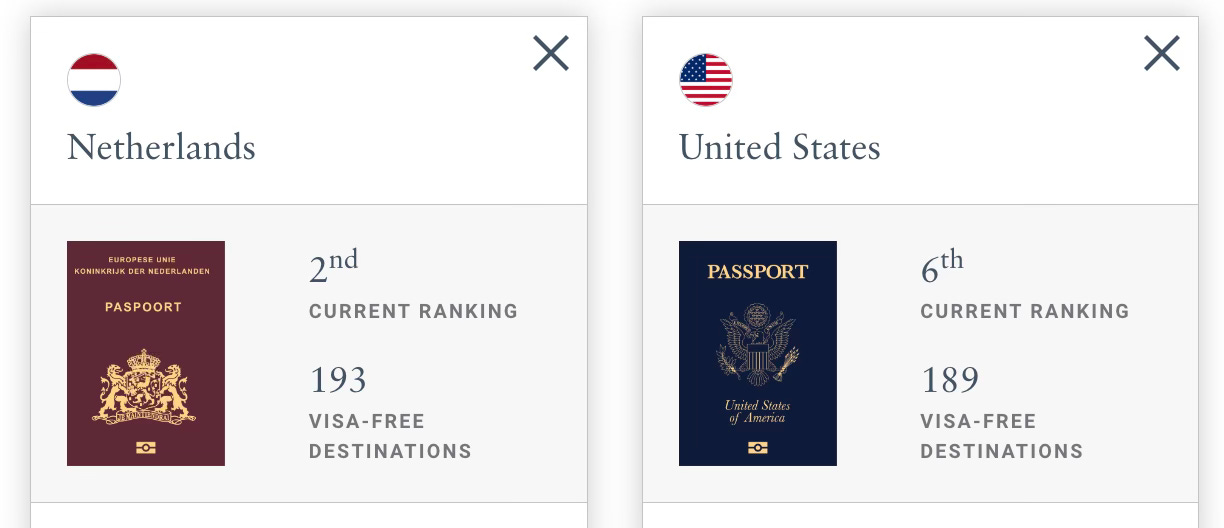

A lot of people have asked me what I will be giving up when I become a Dutch citizen. I find it interesting that they don’t ask me what I will be acquiring in exchange for what I’ll be giving up. But it’s true. There are a few things I will be giving up.

Saying ‘tot ziens’ to America

My American friends often assume that, after the process of naturalisation, I will take on dual citizenship and be able to take advantage of two very useful passports. When they find out that I’m actually required to give up my US citizenship to become Dutch, they often draw back in surprise. When I inform them that not only must I renounce my citizenship, but that I’m frankly looking forward to it – I devilishly relish the idea of giving my home country the middle finger on the way out the door. Then, they recoil more visibly.

The Netherlands does not look kindly on dual citizenship. In fact, they are very Dutch direct about it on their very well-designed government website: “The Government of the Netherlands wants to limit dual citizenship as much as possible.”

There are some exceptions, of course, but none of them apply to me, an extremely privileged foreign knowledge worker who isn’t in any danger of becoming a stateless refugee. However, one of those exceptions could potentially apply to me. If I were to marry a Dutch citizen, then I could keep my American passport. Considering that I haven’t had a date in forever, this is unlikely to occur. (Ladies, you have six months left to save my American citizenship. Single moms welcome.)

Getting rid of everything and starting over, learning the quirky Dutch language, and giving up American citizenship might be hard, but I think it will all be worth it.

Expat or immigrant? Which will it be?

I don’t need to become a Dutch citizen. I could simply become a permanent resident, which would allow me to stay for five more years and provide me with plenty of flexibility to switch to a different job or become a freelancer or even start my own business. It would also allow me to vote in local, municipal elections. Every five years, you just re-up your permanent resident status. This is what most expats do.

However, if I’m a citizen, I’ll be able to vote in broader elections in the Netherlands. How refreshing it will be to choose from a multitude of political parties who are all, by nature, invested in community and cooperation rather than political warfare. Voting isn’t a huge driver for me because in general I trust the political winds of the Netherlands, but I would like to vote.

There is one especially important reason that becoming a full citizen is better than staying as a permanent resident: EU citizenship. Once I’m an EU citizen, I will be able to not just vote in EU elections but to move to any country in Europe if I wish. As someone who already has an eye on retirement, that feels extremely powerful.

I may end up staying in Amsterdam until I die, but having the possibility in my back pocket to be able to retire in Greece or Italy or Finland or Romania or Portugal or Denmark or Sweden – well, you get the idea.

Entrance and exit fees

There is a cost associated with becoming a Dutch citizen. I’ve so far spent €250 on citizenship tests, and I will need to fork over €1,023 more to the kingdom when I submit my formal application. If my application is refused, there will be no refund, but I won’t be refused unless I break some significant laws in the coming months.

There is also a cost to leave America, and it is striking: $2,350. This price is five times higher than other high-income countries. The US State Department indicated last year that they might reduce this fee, perhaps even bringing it to as low as $450. Will that fee reduction happen before I apply to renounce my citizenship in September, when I will need to meet with someone from the US consulate in Amsterdam to ensure that I understand the gravity of my decision? Possibly? Maybe? Hopelijk?

I’m told that America insists on payment for renunciation of your citizenship by credit card only, which may present a problem. I don’t have a credit card. The Dutch are extremely debt averse, and most people here don’t have or want credit cards. I gave up mine last year.

Helaas pindakaas, you can’t ask the US government to send you a Tikkie.

Furthermore

Helaas pindakaas is a very popular saying in Dutch when things go wrong unexpectedly.

Don’t know Tikkie? It’s like Venmo, only better.